TON and granular fees

The Open Network (TON) is a Layer-1 blockchain originally designed by Telegram and now maintained by an independent community. It combines a sharded architecture, asynchronous message passing, and a highly granular fee model to support high-throughput smart-contract execution. At its core is the TON Virtual Machine (TVM), which gives contracts fine-grained, bit-level control over the data stored and transmitted.

TON uses a granular fee model, with fees paid in the network's native currency, Toncoin (TON). Each contract has a TON balance, and messages can carry TON in a way similar to $msg.value$ in the EVM. Fees can be paid from two sources: the contract balance before the incoming message value is credited, or the balance after the message value has been credited. In the first case, the contract must already hold enough TON to cover the fee, independently of the message value. In the second case, the fee is deducted only after the transferred value is added to the contract balance.

In general, there are three types of fees to consider:

Computation fees

Similar to Ethereum, each instruction executed by the TVM has a cost in gas units. The execution cost depends on the gas units consumed during the transaction. The price of one gas unit is fixed in the blockchain configuration and can only be changed by validator voting.

In short, computational fees are directly proportional to the computational fee price and the gas consumed by the computation.$comp\_fee = comp\_fee\_price \times gas\_consumed$ (simplified)

Computational fees must not exceed the message value unless the contract explicitly accepts to pay computational fees out of their own balance (the TVM has a special instruction for that). If the funds attached are insufficient to cover the computational fees, the execution reverts.

Storage fees

This is the amount to be paid for storing the contract on the blockchain.

These fees are directly proportional to the contract's size and accrue every second that the contract is deployed. When the contract receives a message, the storage fees are settled.

$storage\_fee = storage\_fee\_price \times contract\_size\_bits \times seconds\_elapsed\_since\_last\_settle$ (simplified)

Generally, storage fees are paid from the contract's balance before the message value is credited. Consequently, the contract must have enough funds to pay for its own rent. When the balance is insufficient, storage fees accrue as debt and, if not repaid, can eventually cause the contract to be removed from the chain.

Forwarding fees

Forwarding fees are the costs paid for sending messages between contracts.

Forwarding fees are directly proportional to the forwarding fee price and the message size.

$fwd\_fee = fwd\_fee\_price \times msg\_bits$ (simplified)

As for computational fees, the funds attached to the message are generally expected to cover forwarding fees. If a contract is unable to pay forwarding fees, the execution reverts.

Asynchronous messages

TON messages are asynchronous, which means that a contract cannot synchronously query another contract and immediately continue execution based on the result within the same transaction. Instead, responses may be delivered at a later time.

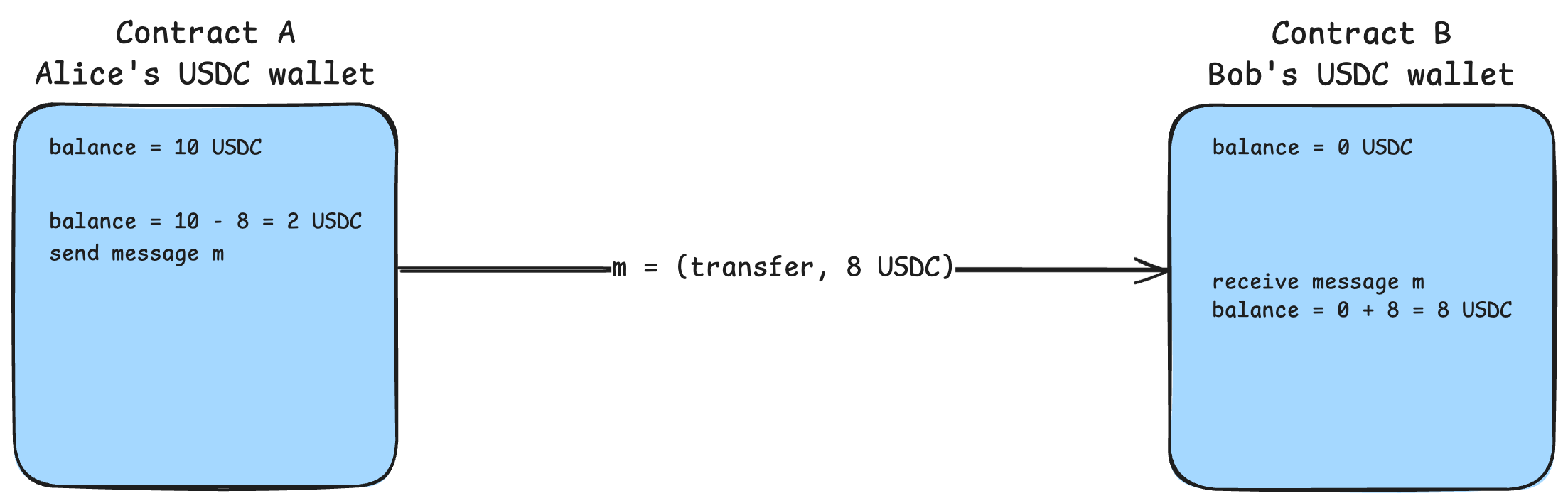

Consider the following example, where Alice's USDC wallet (contract A) sends tokens to Bob's USDC wallet (contract B).

- A holds a balance of 10 USDC and B holds a balance of 0 USDC.

- Alice calls A.transfer(Bob, 8 USDC).

- A computes balance = 10 - 8 = 2 USDC

- A sends a message to B. m = (transfer, 8 USDC)

- B receives m, and increases its balance by computing balance = 0 + 8 = 8 USDC

- The transfer succeeded: A holds a balance of 2 USDC and B holds a balance of 8 USDC.

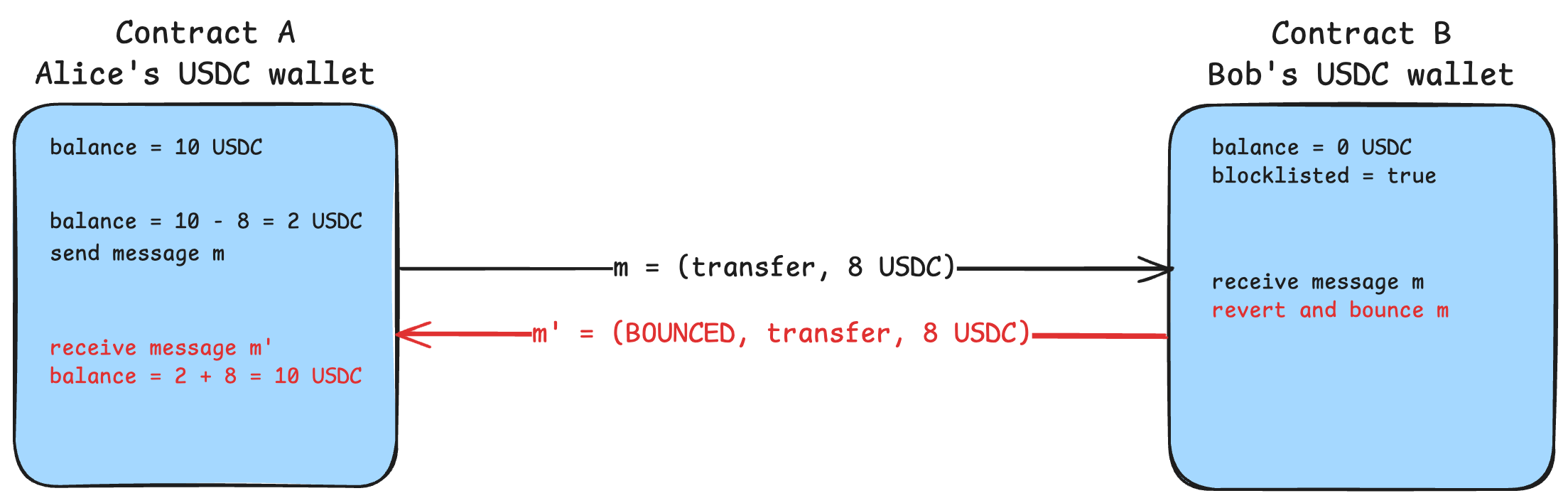

Bouncing messages

Let's now consider the case where B reverts when processing the message sent by A. Differently from the EVM, B reverting does not cause A to atomically revert as well. Consequently, A must implement a mechanism to detect that B has reverted and act accordingly. This is the goal of message bouncing.

If B reverts while processing message m, the message is bounced, which means that m is prepended with a bounced flag and sent back to the sender.

Going back to the example above, assume that Bob's wallet (B) is blocklisted and thus unable to receive funds.

- As above, A sends a message to B. m = (transfer, 8 USDC)

- B receives m and reverts, prepending the bounced flag to m, yielding m' = (BOUNCED, transfer, 8USDC)

- A receives m', detects that it is a bounced message from B, and undoes the transfer by computing balance = 2 + 8 = 10 USDC

- The transfer failed and the state reverted to the initial: A holds a balance of 10 USDC and B holds a balance of 0 USDC.

As shown, bouncing messages and their correct handling is crucial to maintain state consistency.

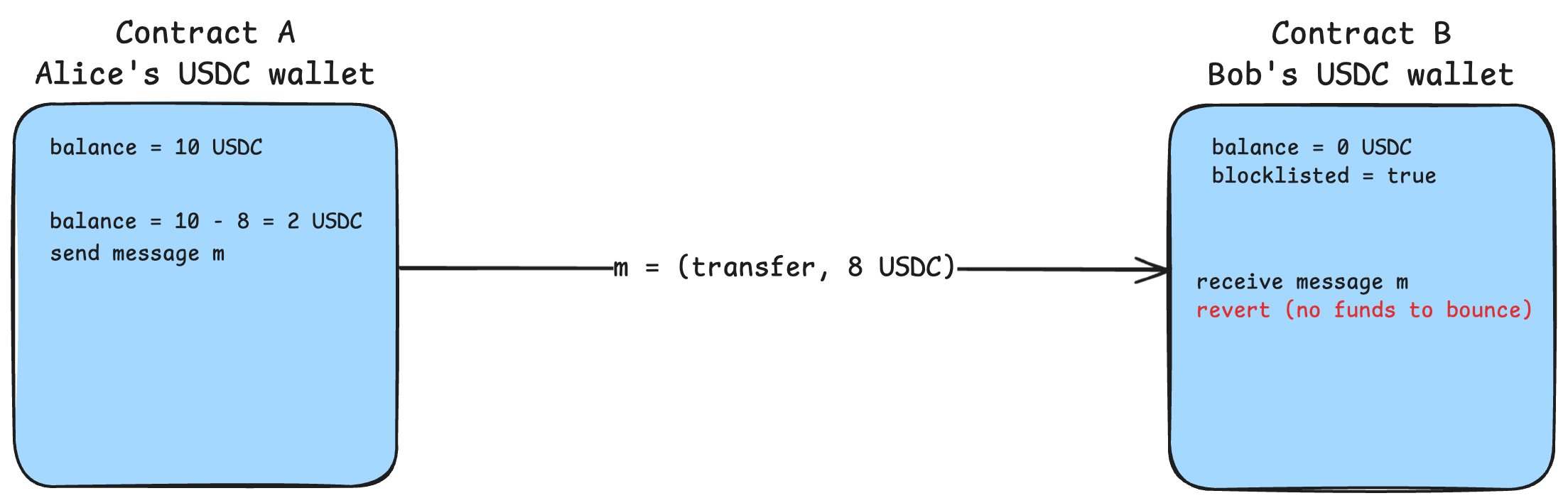

When bouncing fails

We have discovered how important the role of bounced messages is, but we've also noted that sending messages requires sufficient funds. A problematic scenario arises when a contract runs out of balance and is therefore unable to send a bounced message. Consider this situation in the previous example.

- As above, B receives m and reverts. However, B runs out of funds and cannot send the bounced message m' back to A.

- A does not receive m' and cannot detect that B reverted.

- The transfer failed, but the state of A remains unchanged: A holds a balance of 2 USDC and B holds a balance of 0 USDC; 8 USDC have been lost.

Gas estimations are critical

To prevent the scenario described above, it is essential for developers to validate the amount of TON attached to a message at the very beginning of the call path. Contract execution should proceed only if the attached funds are sufficient to cover all the fees for all possible execution branches. This ensures that, regardless of how the execution unfolds, all contracts will end up in a consistent state.

In practice, this means that contracts should conservatively estimate gas usage and explicitly require that:

msg_value ≥ expected_compute_fee + expected_forwarding_fee

Only after this condition is satisfied should the contract proceed with its execution.

Additionally, if the execution flow is expected to deploy a new contract, the estimation must also include enough TON to cover the new contract’s storage fees. In other words, the deployment should leave the contract with sufficient balance to pay its own rent for a period of time adequate to fulfil its purpose.

In order to estimate these fees, developers can leverage the following TVM instructions:

- GETGASFEE: takes as input the units of gas used and returns the corresponding computation fees. Developers can measure the gas consumed by benchmarking the most expensive callpath.

- GETFORWARDFEE: takes as input the message size and returns the forwarding fee paid to send the message. To compute the total forwarding fees, developers should estimate the maximum message size possible and the total number of messages sent in the longest callpath.

Note on TVM 12

Starting with TVM 12, the cost of bounce messages increased due to changes in how bounce messages are serialized and forwarded. In particular, bounce messages now include more contextual data, which increases their size and, consequently, their forwarding fee. Developers should account for higher forwarding costs in callpaths that include bounced messages.

Takeaways

- TON relies on asynchronous messaging, so state consistency across contracts depends on the correct handling of bounced messages rather than atomic reverts.

- Forwarding, computation, and storage fees are charged independently and can come from different balance sources, which makes fee accounting non-trivial.

- If a contract cannot afford to send a bounce message, silent failures can occur, leading to inconsistent states and possible loss of funds.

- Developers must always validate that the attached message value covers both computation and forwarding fees for all possible execution branches before proceeding with execution.

- Starting from TVM 12, bounce paths are more expensive, making conservative fee estimation even more critical.

.png)